- Home

- Thich Nhat Hanh

The Miracle of Mindfulness (Gift Edition) Page 8

The Miracle of Mindfulness (Gift Edition) Read online

Page 8

I. THE CONTEMPLATION OF THE BODY

1. Mindfulness of Breathing

And how does a monk live contemplating the body in the body?

Herein, monks, a monk having gone to the forest, to the foot of a tree or to an empty place, sits down, with his legs crossed, keeps his body erect and his mindfulness alert.

Ever mindful he breathes in, and mindful he breathes out. Breathing in a long breath, he knows “I am breathing in a long breath”; breathing out a long breath, he knows “I am breathing out a long breath”; breathing in a short breath, he knows “I am breathing in a short breath”; breathing out a short breath, he knows “I am breathing out a short breath.”

“Experiencing the whole body, I shall breathe in,” thus he trains himself. “Experiencing the whole body, I shall breathe out,” thus he trains himself. “Calming the activity of the body, I shall breathe in,” thus he trains himself. “Calming the activity of the body, I shall breathe out,” thus he trains himself.

Just as a skillful turner or turner’s apprentice, making a long turn, knows “I am making a long turn,” or making a short turn, knows, “I am making a short turn,” just so the monk, breathing in a long breath, knows “I am breathing in a long breath”; breathing out a long breath, knows “I am breathing out a long breath”; breathing in a short breath, knows “I am breathing in a short breath”; breathing out a short breath, knows “I am breathing out a short breath.” “Experiencing the whole body, I shall breathe in,” thus he trains himself. “Experiencing the whole body, I shall breathe out,” thus he trains himself. “Calming the activity of the body, I shall breathe in,” thus he trains himself. “Calming the activity of the body, I shall breathe out,” thus he trains himself.

Thus he lives contemplating the body in the body internally, or he lives contemplating the body in the body, internally and externally. He lives contemplating origination-factors in the body, or he lives contemplating origination-and-dissolution factors in the body. Or his mindfulness is established with the thought: “The body exists,” to the extent necessary just for knowledge and mindfulness, and he lives detached, and clings to naught in the world. Thus also, monks, a monk lives contemplating the body in the body.

2. The Postures of the Body

And further, monks, a monk knows when he is going “I am going”; he knows when he is standing “I am standing”; he knows when he is sitting “I am sitting”; he knows when he is lying down “I am lying down”; or just as his body is disposed so he knows it.

Thus he lives contemplating the body in the body internally, or he lives contemplating the body in the body externally, or he lives contemplating the body in the body internally and externally. He lives contemplating origination-factors in the body, or he lives contemplating origination-and-dissolution factors in the body. Or his mindfulness is established with the thought: “The body exists,” to the extent necessary just for knowledge and mindfulness, and he lives detached, and clings to naught in the world. Thus also, monks, a monk lives contemplating the body in the body.

3. Mindfulness with Clear Comprehension

And further, monks, a monk, in going forward and back, applies clear comprehension; in looking away, he applies clear comprehension; in bending and in stretching, he applies clear comprehension; in wearing robes and carrying the bowl, he applies clear comprehension; in eating, drinking, chewing, and savoring, he applies clear comprehension; in attending to the calls of nature, he applies clear comprehension; in walking, standing, in sitting, in falling asleep, in waking, in speaking and in keeping silence, he applies clear comprehension.

Thus he lives contemplating the body in the body . . .

4. The Reflection on the Repulsiveness of the Body

And further, monks, a monk reflects on this very body enveloped by the skin and full of manifold impurity, from the soles up, and from the top of the head-hair down, thinking thus: “There are in this body hair of the head, hair of the body, nails, teeth, skin, flesh, sinews, bones, marrow, kidneys, heart, liver, midriff, spleen, lungs, intestines, mesentery, gorge, feces, bile, phlegm, pus, blood, sweat, fat, tears, grease, saliva, nasal mucus, synovial fluid, urine.”

Just as if there were a double-mouthed provision bag full of various kinds of grain such as hill paddy, paddy, green gram, cow-peas, sesame, and husked rice, and a man with sound eyes, having opened that bag, were to take stock of the contents thus: This is hill paddy, this is paddy, this is green gram, this is cowpea, this is sesame, this is husked rice. Just so, monks, a monk reflects on this very body enveloped by the skin and full of manifold impurity, from the soles up, and from the top of the head-hair down, thinking thus: “There are in this body hair of the head, hair of the body, nails, teeth, skin, flesh, sinews, bones, marrow, kidneys, heart, liver, midriff, spleen, lungs, intestines, mesentery, gorge, feces, bile, phlegm, pus, blood, sweat, fat, tears, grease, saliva, nasal mucus, synovial fluid, urine.”

Thus he lives contemplating the body in the body . . .

5. The Reflection on the Material Elements

And further, monks, a monk reflects on this very body, however it be placed or disposed, by way of the material elements: “There are in this body the element of earth, the element of water, the element of fire, the element of wind.”

Just as if, monks, a clever cow-butcher or his apprentice, having slaughtered a cow and divided it into portions, should be sitting at the junction of four high roads, in the same way, a monk reflects on this very body, as it is placed or disposed, by way of the material elements: “There are in this body the elements of earth, water, fire, and wind.”

Thus he lives contemplating the body in the body . . .

6. The Nine Cemetery Contemplations

1. And further, monks, as if a monk sees a body dead one, two, or three days; swollen, blue, and festering, thrown in the charnel ground, he then applies this perception to his own body thus: “Verily, also my own body is of the same nature; such it will become and will not escape it.”

Thus he lives contemplating the body in the body internally, or lives contemplating the body in the body externally, or lives contemplating the body in the body internally and externally. He lives contemplating origination-factors in the body, or he lives contemplating dissolution-factors in the body, or he lives contemplating origination-and-dissolution-factors in the body. Or his mindfulness is established with the thought: “The body exists,” to the extent necessary just for knowledge and mindfulness, and he lives independent, and clings to naught in the world. Thus also, monks, a monk lives contemplating the body in the body.

2. And further, monks, as if a monk sees a body thrown in the charnel ground, being eaten by crows, hawks, vultures, dogs, jackals, or by different kinds of worms, he then applies this perception to his own body thus: “Verily, also my own body is of the same nature; such it will become and will not escape it.”

Thus he lives contemplating the body in the body . . .

3. And further, monks, as if a monk sees a body thrown in the charnel ground and reduced to a skeleton with some flesh and blood attached to it, held together by the tendons . . .

4. And further, monks, as if a monk sees a body thrown in the charnel ground, and reduced to a skeleton, blood-besmeared and without flesh, held together by the tendons . . .

5. And further, monks, as if a monk sees a body thrown in the charnel ground and reduced to a skeleton without flesh and blood, held together by the tendons . . .

6. And further, monks, as if a monk sees a body thrown in the charnel ground and reduced to disconnected bones, scattered in all directions—here a bone of the hand, there a bone of the foot, a shin bone, a thigh bone, the pelvis, spine and skull . . .

7. And further, monks, as if a monk sees a body thrown in the charnel ground, reduced to bleached bones of conch-like color . . .

8. And further, monks, as if a monk sees a body thrown in the charnel ground, reduced to bones, more than a year old, lying in a heap . . .

9. And

further, monks, as if a monk sees a body thrown in the charnel ground, reduced to bones, gone rotten and become dust, he then applies this perception to his own body thus: “Verily, also my own body is of the same nature; such it will become and will not escape it.”

Thus he lives contemplating the body in the body internally, or he lives contemplating the body in the body externally, or he lives contemplating the body in the body internally and externally. He lives contemplating origination-factors in the body, or he lives contemplating dissolution-factors in the body, or he lives contemplating origination-and-dissolution-factors in the body. Or his mindfulness is established with the thought: “The body exists,” to the extent necessary just for knowledge and mindfulness, and he lives detached, and clings to naught in the world. Thus also, monks, a monk lives contemplating the body in the body.

II. THE CONTEMPLATION OF FEELING

And how, monks, does a monk live contemplating feelings in feelings?

Herein, monks, a monk when experiencing a pleasant feeling knows, “I experience a pleasant feeling”; when experiencing a painful feeling, he knows, “I experience a painful feeling”; when experiencing a neither pleasant nor painful feeling, he knows, “I experience a neither pleasant nor painful feeling”; when experiencing a pleasant worldly feeling, he knows, “I experience a pleasant worldly feeling”; when experiencing a pleasant spiritual feeling, he knows, “I experience a pleasant spiritual feeling”; when experiencing a painful worldly feeling, he knows, “I experience a painful worldly feeling”; when experiencing a painful spiritual feeling, he knows, “I experience a painful spiritual feeling”; when experiencing a neither pleasant nor painful worldly feeling, he knows, “I experience a neither pleasant nor painful worldly feeling”; when experiencing a neither pleasant nor painful spiritual feeling, he knows, “I experience a neither pleasant nor painful spiritual feeling.”

Thus he lives contemplating feelings in feelings internally, or he lives contemplating feelings in feelings externally, or he lives contemplating feelings in feelings internally and externally. He lives contemplating origination-factors in feelings, or he lives contemplating dissolution-factors in feelings, or he lives contemplating origination-and-dissolution factors in feelings. Or his mindfulness is established with the thought, “Feeling exists,” to the extent necessary just for knowledge and mindfulness, and he lives detached, and clings to naught in the world. Thus, monks, a monk lives contemplating feelings in feelings.

III. THE CONTEMPLATION OF CONSCIOUSNESS

And how, monks, does a monk live contemplating consciousness in consciousness?

Herein, monks, a monk knows the consciousness with lust, as with lust; the consciousness without lust, as without lust; the consciousness with hate, as with hate; the consciousness without hate, as without hate; the consciousness with ignorance, as with ignorance; the consciousness without ignorance, as without ignorance; the shrunken state of consciousness as the shrunken state; the distracted state of consciousness as the distracted state; the developed state of consciousness as the developed state; the undeveloped state of consciousness as the undeveloped state; the state of consciousness with some other mental state superior to it, as the state with something mentally higher; the state of consciousness with no other mental state superior to it, as the state with nothing mentally higher; the concentrated state of consciousness as the concentrated state; the unconcentrated state of consciousness as the unconcentrated state; the freed state of consciousness as the freed state; and the unfreed state of unconsciousness as the unfreed.

Thus he lives contemplating consciousness in consciousness internally or he lives contemplating consciousness in consciousness externally, or he lives contemplating consciousness in consciousness internally and externally. He lives contemplating origination-factors in consciousness, or he lives contemplating dissolution-factors in consciousness, or he lives contemplating origination-and-dissolution-factors in consciousness. Or his mindfulness is established with the thought, “Consciousness exists,” to the extent necessary just for knowledge and mindfulness, and he lives detached and clings to naught in the world. Thus, monks, a monk lives contemplating consciousness in consciousness.

IV. THE CONTEMPLATION OF MENTAL OBJECTS

1. The Five Hindrances

And how, monks, does a monk live contemplating mental objects in mental objects?

Herein, monks, a monk lives contemplating mental objects in the mental objects of the five hindrances.

How, monks, does a monk live contemplating mental objects in the mental objects of the five hindrances?

Herein, monks, a monk, when sense-desire is present, knows, “There is sense-desire in me,” or when sense-desire is not present, he knows, “There is no sense-desire in me.” He knows how the arising of the nonarisen sense-desire comes to be; he knows how the abandoning of the arisen sense-desire comes to be; and he knows how the nonarising in the future of the abandoned sense-desire comes to be.

When anger is present, he knows, “There is anger in me,” or when anger is not present, he knows, “There is no anger in me.” He knows how the arising of the nonarisen anger comes to be; he knows how the abandoning of the arisen anger comes to be; and he knows how the nonarising in the future of the abandoned anger comes to be.

When sloth and torpor are present, he knows, “There are sloth and torpor in me,” and when sloth and torpor are not present, he knows, “There are no sloth and torpor in me.” He knows how the arising of the nonarisen sloth and torpor comes to be; he knows how the abandoning of the arisen sloth and torpor comes to be; and he knows how the nonarising in the future of the abandoned sloth and torpor comes to be.

When agitation and scruples are present, he knows, “There are agitation and scruples in me,” or when agitation and scruples are not present, he knows, “There are no agitation and scruples in me.” He knows how the arising of the nonarisen agitation and scruples comes to be; he knows how the abandoning of the arisen agitation and scruples comes to be; and he knows how the nonarising in the future of the abandoned agitation and scruples comes to be.

When doubt is present, he knows, “There is doubt in me,” or when doubt is not present, he knows, “There is no doubt in me.” He knows how the arising of the nonarisen doubt comes to be; he knows how the abandoning of the arisen doubt comes to be; he knows how the nonarising in the future of the abandoned doubt comes to be.

Thus he lives contemplating mental objects in mental objects internally, or he lives contemplating mental objects in mental objects externally, or he lives contemplating mental objects in mental objects internally and externally. He lives contemplating origination-factors in mental objects, or he lives contemplating dissolution-factors in mental objects, or he lives contemplating origination-and-dissolution-factors in mental objects. Or his mindfulness is established with the thought, “Mental objects exist,” to the extent necessary just for knowledge and mindfulness, and he lives detached, and clings to naught in the world. Thus also, monks, a monk lives contemplating mental objects in the mental objects of the five hindrances.

2. The Five Aggregates of Clinging

And further, monks, a monk lives contemplating mental objects in the mental objects of the five aggregates of clinging.

How, monks, does a monk live contemplating mental objects in the mental objects of the five aggregates of clinging?

Herein, monks, a monk thinks, “Thus is material form; thus is the arising of material form; and thus is the disappearance of material form. Thus is feeling; thus is the arising of feeling; thus is the disappearance of feeling. Thus is perception; thus is the arising of perception; thus is the disappearance of perception. Thus are formations; thus is the arising of formations; and thus is the disappearance of formations. Thus is consciousness; thus is the arising of consciousness; and thus is the disappearance of consciousness.”

Thus he lives contemplating mental objects in mental objects internally, or he lives contemplating mental objects in mental object

s externally, or he lives contemplating mental objects in mental objects internally and externally. He lives contemplating origination-factors in mental objects, or he lives contemplating dissolution-factors in mental objects, or he lives contemplating origination-and-dissolution-factors in mental objects. Or his mindfulness is established with the thought, “Mental objects exist,” to the extent necessary just for knowledge and mindfulness, and he lives detached, and clings to naught in the world. Thus also, monks, a monk lives contemplating mental objects in the mental objects of the five aggregates of clinging.

3. The Six Internal and the Six External Sense-Bases

And further, monks, a monk lives contemplating mental objects in the mental objects of the six internal and the six external sense-bases.

How, monks, does a monk live contemplating mental objects in the mental objects of the six internal and the six external sense-bases?

Herein, monks, a monk knows the eye and visual forms, and the fetter that arises dependent on both (the eye and forms); he knows how the arising of the nonarisen fetter comes to be; he knows how the abandoning of the arisen fetter comes to be; and he knows how the nonarising in the future of the abandoned fetter comes to be.

He knows the ear and sounds . . . the nose and smells . . . the tongue and flavors . . . the body and tactile objects . . . the mind and mental objects, and the fetter that arises dependent on both; he knows how the abandoning of the nonarisen fetter comes to be; and he knows how the nonarising in the future of the abandoned fetter comes to be.

Thus, monks, the monk lives contemplating mental objects in mental objects internally, or he lives contemplating mental objects in mental objects externally, or he lives contemplating mental objects in mental objects internally and externally. He lives contemplating origination-factors in mental objects, or he lives contemplating dissolution-factors in mental objects, or he lives contemplating origination-and-dissolution-factors in mental objects. Or his mindfulness is established with the thought, “Mental objects exist,” to the extent necessary just for knowledge and mindfulness, and he lives detached, and clings to naught in the world. Thus, monks, a monk lives contemplating mental objects in the mental objects of the six internal and the six external sense-bases.

How to Love

How to Love The Miracle of Mindfulness

The Miracle of Mindfulness The Miracle of Mindfulness (Gift Edition)

The Miracle of Mindfulness (Gift Edition) The Blooming of a Lotus

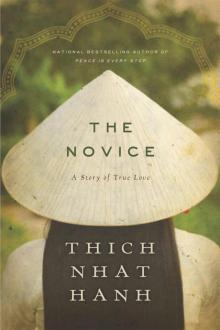

The Blooming of a Lotus The Novice

The Novice