- Home

- Thich Nhat Hanh

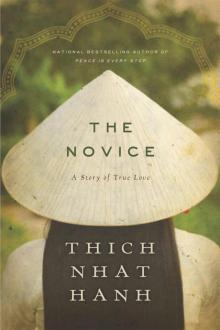

The Novice

The Novice Read online

The Novice

A Story of True Love

THICH NHAT HANH

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Chapter One - Abandoned Child

Chapter Two - Humiliation

Chapter Three - Stepping into Freedom

Chapter Four - Delirium

Chapter Five - Unbearable Injustice

Chapter Six - Sharpening the Sword

Chapter Seven - Diamond Heart

Chapter Eight - Great Vow

Chapter Nine - Loving Heart

A Brief Note on the Legend of Quan Am Thi Kinh

Thi Kinh’s Legacy by Sister Chan Khong

Practicing Love by Thich Nhat Hanh

About the Author

Also by Thich Nhat Hanh

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

Chapter One

ABANDONED CHILD

Kinh Tam had just finished sounding the last bell of the evening chant when the young novice heard the wailing of a baby. Kinh Tam thought, “That’s strange!” Releasing the bell, the novice quietly stepped over to the doorway of the bell tower and looked down at the hillside just in time to see Thi Mau in a light brown nam than, a long shirt commonly worn by Vietnamese women, holding a crying newborn in her arms. She gazed up in the novice’s direction.

An alarming thought flashed in Kinh Tam’s mind. “Thi Mau must have given birth to the child and is now coming up here to leave it in my care.”

Waves of turbulent feelings arose rapidly within. Novice Kinh Tam reviewed the precarious situation. “I’ve taken the monastic vows of a novice. I’ve just been accused of having a sexual affair with Thi Mau, making her pregnant, and not owning up to the alleged offense.” The thoughts tumbled on. “Who can possibly understand the predicament I’m facing? Doesn’t anyone see the great injustice being done to me? Even though my teacher, the abbot of this temple, loves me, even though my two Dharma brothers care deeply for me, who knows whether they have doubts about my heart? And now the baby is here. Stubbornly refusing to bring the newborn to its true father, Thi Mau has brought it here to the temple. Everyone who already suspected that I’m the child’s father will surely misconstrue my taking in the newborn. They will say I’ve admitted my guilt. What will my teacher think? How will my Dharma brothers react? And the people in the village?”

Novice Kinh Tam finally concluded, “Maybe I should go down to meet Thi Mau and advise her to be brave, to tell her parents the name of the real father, and to take the baby to him instead.” Kinh Tam stepped down from the bell tower, all the while silently invoking the name of Buddha. The novice had a lot of confidence in the healing energy of loving-kindness embodied by the Buddha. Surely the Buddha’s wisdom could be a guide through this very difficult period. The novice intended to use gentle, kind words to advise Thi Mau, to help her see a more admirable way to handle this situation. But as the novice stepped out of the bell tower, Thi Mau had already run away, quite far down the hillside. She shot through the temple gates like an arrow and disappeared into the hills thick with evergreens. At that very moment, the newborn, wrapped in many layers of white cotton cloth and abandoned on the steps leading to the bell tower, burst out in heart-wrenching cries.

Kinh Tam quickly ran over to pick up the baby. From deep within, the novice felt the budding of a new love. The nurturing instinct sprang up as a powerful source of energy. “This child is not being cared for or acknowledged by anyone. His father does not recognize him, and his own mother has just abandoned him. His paternal grandparents don’t even know he is present on this Earth. If I don’t take him into my care, then who will?” thought the novice. “I claim to be a monk, a person practicing to be more compassionate, so how can I have the right or the heart to desert this child?” The novice grew adamant. “Let them gossip, let them suspect, let them curse me! The newborn needs someone to take care of him and raise him. If I don’t do it, then who will?”

With tears streaming down, Kinh Tam lovingly hugged and cuddled the baby. The novice’s heart was filled at once with both great sadness and the sweet nectar of compassion. Kinh Tam sensed that the baby was getting hungry and thought immediately of Uncle and Aunt Han (“Rarity”), a couple living in the village below the hill on which the temple stood. Aunt Han had given birth to a baby just a fortnight ago. The most important thing to do now was to take this baby down to the village and beg that he be nursed. Uncle and Aunt Han regularly attended temple ser vices, and they were on good terms with all the novices. Surely the good woman would be willing to share some of her milk to feed this unfortunate child.

Kinh Tam wrapped the cotton layers more snugly around the baby to keep him warm. Then the novice carried the little baby through the gate and down along the path leading to the village below, fully attentive to each step and each breath.

“Tomorrow morning, my teacher and my two Dharma brothers will undoubtedly question me for taking in the baby,” the novice pondered silently. “And I will answer: Dear teacher, you have taught me that the merit to be gained through building an elaborate temple nine stories high cannot compare to that of saving the life of one person. Taking your advice to heart, I have taken in this baby to rear. I ask you, dear teacher and dear Dharma brothers, to have compassion. The baby has been neglected, abandoned, and rejected by everyone. Thi Mau left him on the steps of the bell tower last evening and then ran away without saying anything. If I had not taken him in and cared for him, the child would have died.

“‘Homage to Avalokiteshvara, the bodhisattva giving aid in desperate crises.’ Everyone who comes to the temple always recites verses like this with much devotion. Every one of us needs to take refuge in the Bodhisattva of Great Compassion and Loving-kindness. Yet very few of us actually practice nurturing and offering great compassion and loving-kindness in our daily lives.” The novice continued reflecting. “I’m a disciple of the Buddha and the bodhisattvas; I have to practice in accord with their aspirations. I must be able to cultivate and embody the energies of great compassion and loving-kindness that are within me.”

At that time, although Kinh Tam was just twenty-four years old, the novice had already twice endured great injustice. The first was being accused of attempting to kill another person. The second was being said to have transgressed the monastic vows in sleeping with Mau, the daughter of the richest family in the village, and making her pregnant. Two instances of very grave injustice. But Kinh Tam could still bear it, because the novice knew the practice of inclusiveness (magnanimity) and had learned ways to nourish loving-kindness and compassion.

In fact, the novice was not a young man at all. Kinh Tam was actually a daughter of the Ly (“Plum”) family in another province. Her parents had named her Kinh (“Reverence”). Because she so strongly wished to live the monastic life, Kinh had disguised herself as a young man in order to be ordained. Buddhism had entered Giao Chau, the ancient name for what is now Vietnam, around two hundred years earlier, and the temples there were only receiving men for ordination.

Kinh had heard that long ago in India there had been numerous temples in which women could become Buddhist nuns. She often wondered, “How much longer will we have to wait before we have a temple for nuns in this country?”

She came to Dharma Cloud Temple, one of the most beautiful temples in the land, to be ordained and to live the monastic life. The temple was in the Giao Chi district, six days’ travel from her home village in Cuu Chan district. Kinh hid the fact from her parents that she was practicing at Dharma Cloud Temple. She knew that if they were to learn of her ordination and whereabouts, they would intervene and beseech her to return home to them.

Just to have the teacher find out that she was a girl in disguise would be enou

gh to have her expelled from the temple. And if she were to become unable to continue the monastic life, the suffering would be too unbearable.

From early childhood, Kinh had been very much a tomboy, always joining in the games of boys. Her parents dressed her in little boys’ outfits. As she got older, they received permission for Kinh to join a classical Chinese class for young boys with the village teacher, named Bai (“Bowing”). Kinh studied very well and received better grades than many of the boys in her class.

Kinh was polite, composed, and sociable, but she was no pushover. Kinh refused to apologize if she saw that she was not at fault, even when asked to by her teacher or her parents. She would respectfully join her palms together and reason, “I cannot apologize, since I did not do anything wrong.”

Some remarked that Kinh was stubborn. Maybe she was, but what could she do about the way she was? At that time, Kinh was an only child, quite cherished and, yes, a bit spoiled by her parents. This changed, though, when Kinh was seven years old and her mother gave birth to her baby brother, whom they named Chau (“Jewel”).

Kinh grew more beautiful with each passing year. When she turned sixteen, many families offered their sons in marriage. Her parents had refused them all— partly because these families did not have the same social status as they did, but also because they were not yet ready to let their daughter go. However, when an offer came from the parents of Thien Si (“Good Scholar”), Kinh’s parents dropped all hesitation and accepted Thien Si was a son of the Dao family. At the time of the offer, he was a college student studying at the Dai Tap University and reputedly a very good student. Thien Si’s parents had much prestige in the district and could trace their lineage back several centuries.

Kinh was nineteen years old and felt she was too young to get married. She had graduated from the Tieu Tap School and already was accepted at Dai Tap University, but her parents forbade her to attend. A woman’s role was to get married and raise a family, and Kinh’s parents did not wish to send her off to school.

Not having much choice in the matter, Kinh had resigned herself to continue her education by self-study at home. She read the classical Confucian Four Books and Five Classics, and also had access to religious books. The greatest fortune in her life was that she had the chance to read the sutra texts of the Buddha. She read The Sutra of Forty-Two Chapters, The Prajnaparamita in Eight Thousand Lines, The Collection on the Six Paramitas by Zen Master Tang Hoi, and Dispelling Doubts by Mouzi.

Teacher Bai was greatly interested in Buddhism, and it was he who lent those sutras and books to Kinh. Once, he even allowed her to visit his home and serve tea to three Buddhist monks whom he had invited over in order to offer them the midday meal and donations of other basic items. In her first encounter with monastics, Kinh was awestruck. The monks wore simple brown robes, and their heads were cleanly shaven. Their bearing was gentle, calm, and relaxed, while their voices conveyed much compassion. Kinh deeply wished to be able to live such a life. But she knew that she could not realize this dream, since in her country temples for nuns simply did not exist.

While reading the sutra on the six perfections, Kinh was often moved to tears. She learned of the Buddha’s life and of the practices of the six perfections—generosity, mindfulness trainings, inclusiveness (magnanimity), diligence, meditation, and insight. The monastic life appealed so much to her. She saw that a monastic’s heart was filled with the abundant energy of love, compassion, inclusiveness, and diligence. She regretted that she had not been born a boy and thus able to live this beautiful way of life.

And now Kinh’s own parents had agreed to Thien Si’s parents’ proposal for marriage. Girls grew up and eventually had to get married. That was just the way things went in those days. How could she go against such a strong tradition? She hoped Thien Si would be easygoing and would not object to her yearning for knowledge or her desire to practice Buddhism.

And so, in the following spring, twenty-year-old Kinh was married into the Dao family. Thien Si was an intelligent young man who was gentle and did well in his studies. At the same time, he was a bit oversensitive, tended to indulge himself, and was not very strong or stable mentally. Many times Kinh had to gently urge him to wake up, eat, sleep, and do his studies with more regularity, but often he just could not do it, however hard he tried, even just to please her. Her in-laws slowly began to look askance at how Thien Si seemed to spend more and more of his time affectionately idle by her side. Kinh had done her best to be an ideal daughter-in-law, as her own mother had taught her to be. The last to sleep, the earliest to rise, tending to all household chores, giving utmost care to her husband’s parents—there was no oversight for which Thien Si’s parents could have criticized her. But they felt as if she had stolen the affection of their precious only son from them, and they bitterly resented her. For Thien Si’s part, he seemed to live less like a person in his own right and more like someone else’s shadow.

Chapter Two

HUMILIATION

Late one night as Kinh was doing some mending, Thien Si was sitting nearby, studying. It was already quite late, but he had persisted in his reading. He then fell asleep next to his young wife. Looking over at him, Kinh saw several strands of hair in his beard growing crudely against the general direction of the rest. With the intention of trimming those few strands, she raised her sewing scissors to do so.

Unfortunately Thien Si woke up at that very moment, and with his mind still muddled from being half asleep, he saw Kinh bringing the sharp scissors toward his throat and thought she was about to kill him. Utterly terrified, Thien Si screamed for help. His parents, still awake in their bedroom next door, came running in.

They yelled, “What happened?”

Thien Si related the incident of waking to the sight of his wife putting her scissors to his throat. Both his parents exploded with rage. They accused Kinh of trying to kill her own husband. They completely refused to listen to any of her pleas for justice.

“Good grief! Why did we bring this nuisance into the family? She’s a saucy daughter-in-law, a flirt, a wanton, evil woman trying to kill her husband, so that she can be with another man!” screamed the old woman.

Kinh turned toward her husband, earnestly pleading with him to clear her of his parents’ false accusations. But Thien Si, overwhelmed by a state of total trauma, said nothing. He sat there crying like a man who had lost his mind altogether. Thien Si could not take control of the situation at all. He sat there like a wretched victim, totally incapable of even a tiny response.

The next morning Thien Si’s parents sent a house servant to call Kinh’s parents over. They seethed, “We do not dare to keep your daughter in our family any longer. Luckily, Thien Si woke up in time or else he would have lost his life. Young women these days are so deceitful. Their outer appearance seems gentle and meek, but deep inside they are hostile and malicious. Who knows, maybe she has fallen for another young man! We return her to you. Our family does not have enough ‘good fortune’ to keep this burden any longer!”

Kinh’s parents looked over to their daughter. It was only then that she was given the chance to explain clearly what had transpired. Her voice was steady and full of respect.

Kinh’s father turned to Thien Si’s parents and said, “I cannot ever imagine our daughter being a murderous person. Both of you have unjustly accused her. Our daughter is a most kindhearted person.”

Thien Si’s mother pursed her lips, refusing to believe in Kinh’s explanation, and demanded that Kinh go back home to her parents.

Kinh’s mother gently prodded her daughter, “You have made a foolish mistake! You need now to bow to your parents-in-law and your husband and beg for their forgiveness.”

Kinh refused. She politely answered, “I didn’t do anything foolish. All I wanted to do was to trim the few stray hairs in my husband’s beard. I have no heart to kill anyone. If I were at fault, I would be more than willing to bow down. But I know with all certainty that I did no wrong, so I cannot do

as you advise.”

And so Kinh followed her parents back home. On leaving, she only slightly bent her head toward everyone, but did not bow low. Thien Si sat silent as a statue. He had no reaction of any kind.

Kinh knew her parents were unhappy, not only be- cause of the abrupt end of her marital life, but also because of the scandal. Personally Kinh did not feel very sad. She felt no anger toward Thien Si or his parents, but was more disappointed in the way people interacted in general. People, it seemed, were always allowing jealousy, sadness, anger, and pride to determine their behavior. So much suffering was caused by misunderstandings and erroneous perceptions about one another.

In her married life over the past year, Kinh had experienced just a handful of happy moments and plenty of difficult ones. Thien Si did not know how to really live his life. He thought only of exams and of being a government official. He did not know how to appreciate the gift of living with his loved ones. To him, literature and academic studies were just a means to advance him in society and were not in themselves sources of happiness in life. Many times Kinh had struck up conversations with him on literature and other subjects, but he was only interested in the respect he could gain through his studies and not in any inherent value they possessed. He particularly disliked discussions on Taoism and Buddhism. To him, there was only one discipline worthy of being called a religion, and that was Confucianism.

After returning to her parents’ home, Kinh was immediately more relaxed and carefree. Besides caring for her parents, Kinh focused on studying Buddhism and overseeing the studies of her younger brother, Chau. She spent all her free time teaching herself to do sitting meditation and slow walking meditation.

How to Love

How to Love The Miracle of Mindfulness

The Miracle of Mindfulness The Miracle of Mindfulness (Gift Edition)

The Miracle of Mindfulness (Gift Edition) The Blooming of a Lotus

The Blooming of a Lotus The Novice

The Novice