- Home

- Thich Nhat Hanh

The Miracle of Mindfulness (Gift Edition)

The Miracle of Mindfulness (Gift Edition) Read online

CONTENTS

Translator’s Preface by Mobi Ho

ONE

The Essential Discipline

TWO

The Miracle Is to Walk on Earth

THREE

A Day of Mindfulness

FOUR

The Pebble

FIVE

One Is All, All Is One: The Five Aggregates

SIX

The Almond Tree in Your Front Yard

SEVEN

Three Wondrous Answers

Exercises in Mindfulness

Thich Nhat Hanh: Seeing with the Eyes of Compassion

by Jim Forest

Selection of Buddhist Sutras

Chronology of Thich Nhat Hanh’s Life

TRANSLATOR’S PREFACE

The Miracle of Mindfulness was originally written in Vietnamese as a long letter to Brother Quang, a main staff member of the School of Youth for Social Service in South Vietnam in 1974. Its author, the Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh, had founded the School in the 1960s as an outgrowth of “engaged Buddhism.” It drew young people deeply committed to acting in a spirit of compassion. Upon graduation, the students used the training they received to respond to the needs of peasants caught in the turmoil of the war. They helped rebuild bombed villages, teach children, set up medical stations, and organize agricultural cooperatives.

The workers’ methods of reconciliation were often misunderstood in the atmosphere of fear and mistrust engendered by the war. They persistently refused to support either armed party and believed that both sides were but the reflection of one reality, and the true enemies were not people, but ideology, hatred, and ignorance. Their stance threatened those engaged in the conflict, and in the first years of the School, a series of attacks were carried out against the students. Several were kidnapped and murdered. As the war dragged on, even after the Paris Peace Accords were signed in 1973, it seemed at times impossible not to succumb to exhaustion and bitterness. Continuing to work in a spirit of love and understanding required great courage.

From exile in France, Thich Nhat Hanh wrote to Brother Quang to encourage the workers during this dark time. Thay Nhat Hanh (“Thay,” the form of address for Vietnamese monks, means “teacher”) wished to remind them of the essential discipline of following one’s breath to nourish and maintain calm mindfulness, even in the midst of the most difficult circumstances. Because Brother Quang and the students were his colleagues and friends, the spirit of this long letter that became The Miracle of Mindfulness is personal and direct. When Thay speaks here of village paths, he speaks of paths he had actually walked with Brother Quang. When he mentions the bright eyes of a young child, he mentions the name of Brother Quang’s own son.

I was living as an American volunteer with the Vietnamese Buddhist Peace Delegation in Paris when Thay was writing the letter. Thay headed the delegation, which served as an overseas liaison office for the peace and reconstruction efforts of the Vietnamese Buddhists, including the School of Youth for Social Service. I remember late evenings over tea, when Thay explained sections of the letter to delegation members and a few close friends. Quite naturally, we began to think of other people in other countries who might also benefit from the practices described in the book.

Thay had recently become acquainted with young Buddhists in Thailand who had been inspired by the witness of engaged Buddhism in Vietnam. They too wished to act in a spirit of awareness and reconciliation to help avert the armed conflict erupting in Thailand, and they wanted to know how to work without being overcome by anger and discouragement. Several of them spoke English, and we discussed translating Brother Quang’s letter. The idea of a translation took on a special poignancy when the confiscation of Buddhist publishing houses in Vietnam made the project of printing the letter as a small book in Vietnam impossible.

I happily accepted the task of translating the book into English. For nearly three years, I had been living with the Vietnamese Buddhist Peace Delegation, where day and night I was immersed in the lyrical sound of the Vietnamese language. Thay had been my “formal” Vietnamese teacher; we had slowly read through some of his earlier books, sentence by sentence. I had thus acquired a rather unusual vocabulary of Vietnamese Buddhist terms. Thay, of course, had been teaching me far more than language during those three years. His presence was a constant gentle reminder to return to one’s true self, to be awake by being mindful.

As I sat down to translate The Miracle of Mindfulness, I remembered the episodes during the past years that had nurtured my own practice of mindfulness. There was the time I was cooking furiously and could not find a spoon I’d set down amid a scattered pile of pans and ingredients. As I searched here and there, Thay entered the kitchen and smiled. He asked, “What is Mobi looking for?” Of course, I answered, “The spoon! I’m looking for a spoon!” Thay answered, again with a smile, “No, Mobi is looking for Mobi.”

Thay suggested I do the translation slowly and steadily, in order to maintain mindfulness. I translated only two pages a day. In the evenings, Thay and I went over those pages, changing and correcting words and sentences. Other friends provided editorial assistance. It is difficult to describe the actual experience of translating his words, but my awareness of the feel of pen and paper, awareness of the position of my body and of my breath enabled me to see most clearly the mindfulness with which Thay had written each word. As I watched my breath, I could see Brother Quang and the workers of the School of Youth for Social Service. More than that, I began to see that the words held the same personal and lively directness for any reader because they had been written in mindfulness and lovingly directed to real people. As I continued to translate, I could see an expanding community—the School’s workers, the young Thai Buddhists, and many other friends throughout the world.

When the translation was completed, we typed it, and Thay printed a hundred copies on the tiny offset machine squeezed into the delegation’s bathroom. Mindfully addressing each copy to friends in many countries was a happy task for delegation members.

Since then, like ripples in a pond, The Miracle of Mindfulness has traveled far. It has been translated into several other languages and has been printed or distributed on every continent in the world. One of the joys of being the translator has been to hear from many people who have discovered the book. I once met someone in a bookstore who knew a student who had taken a copy to friends in the Soviet Union. And recently, I met a young Iraqi student in danger of being deported to his homeland, where he faces death for his refusal to fight in a war he believes cruel and senseless; he and his mother have both read The Miracle of Mindfulness and are practicing awareness of the breath. I have learned, too, that proceeds from the Portuguese edition are being used to assist poor children in Brazil. Prisoners, refugees, health-care workers, educators, and artists are among those whose lives have been touched by this little book. I often think of The Miracle of Mindfulness as something of a miracle itself, a vehicle that continues to connect lives throughout the world.

American Buddhists have been impressed by the natural and unique blending of Theravada and Mahayana traditions, characteristic of Vietnamese Buddhism, which the book expresses. As a book on the Buddhist path, The Miracle of Mindfulness is special because its clear and simple emphasis on basic practice enables any reader to begin a practice of his or her own immediately. Interest in the book, however, is not limited to Buddhists. It has found a home with people of many different religious traditions. One’s breath, after all, is hardly attached to any particular creed.

Those who enjoy this book will likely be interested in other books by Thich Nhat Hanh which have been translated into English.

His books in Vietnamese, including short stories, novels, essays, historical treatises on Buddhism and poetry, number in the dozens. While several of his earlier books in English are no longer in print, more recent works available in translation include A Guide to Walking Meditation, Being Peace, and The Sun My Heart.

Denied permission to return to Vietnam, Thich Nhat Hanh spends most of the year living in Plum Village, a community he helped found in France. There, under the guidance of the same Brother Quang to whom The Miracle of Mindfulness was originally addressed years ago, community members tend hundreds of plum trees. Profits from the sales of their fruit are used to assist hungry children in Vietnam. In addition, Plum Village is open every summer to visitors from around the world who wish to spend a month of mindfulness and meditation. In recent years, Thich Nhat Hanh has also made annual visits to the United States and Canada to conduct week-long retreats organized by the Buddhist Peace Fellowship.

I would like to express special gratitude to Beacon Press for having the vision to print The Miracle of Mindfulness. I hope that each new person whom it reaches will sense that the book is addressed as personally to him or her as it was to Brother Quang and the workers of the School of Youth for Social Service.

Mobi Ho

August 1987

ONE

The Essential Discipline

Yesterday Allen came over to visit with his son Joey. Joey has grown so quickly! He’s already seven years old and is fluent in French and English. He even uses a bit of slang he’s picked up on the street. Raising children here is very different from the way we raise children at home. Here parents believe that “freedom is necessary for a child’s development.” During the two hours that Allen and I were talking, Allen had to keep a constant eye on Joey. Joey played, chattered away, and interrupted us, making it impossible to carry on a real conversation. I gave him several picture books for children but he barely glanced at them before tossing them aside and interrupting our conversation again. He demands the constant attention of grown-ups.

Later, Joey put on his jacket and went outside to play with a neighbor’s child. I asked Allen, “Do you find family life easy?” Allen didn’t answer directly. He said that during the past few weeks, since the birth of Ana, he had been unable to sleep any length of time. During the night, Sue wakes him up and—because she is too tired herself—asks him to check to make sure Ana is still breathing. “I get up and look at the baby and then come back and fall asleep again. Sometimes the ritual happens two or three times a night.”

“Is family life easier than being a bachelor?” I asked. Allen didn’t answer directly. But I understood. I asked another question: “A lot of people say that if you have a family you’re less lonely and have more security. Is that true?” Allen nodded his head and mumbled something softly. But I understood.

Then Allen said, “I’ve discovered a way to have a lot more time. In the past, I used to look at my time as if it were divided into several parts. One part I reserved for Joey, another part was for Sue, another part to help with Ana, another part for household work. The time left over I considered my own. I could read, write, do research, go for walks.

“But now I try not to divide time into parts anymore. I consider my time with Joey and Sue as my own time. When I help Joey with his homework, I try to find ways of seeing his time as my own time. I go through his lesson with him, sharing his presence and finding ways to be interested in what we do during that time. The time for him becomes my own time. The same with Sue. The remarkable thing is that now I have unlimited time for myself!”

Allen smiled as he spoke. I was surprised. I knew that Allen hadn’t learned this from reading any books. This was something he had discovered for himself in his own daily life.

WASHING THE DISHES

TO WASH THE DISHES

Thirty years ago, when I was still a novice at Tu Hieu Pagoda, washing the dishes was hardly a pleasant task. During the Season of Retreat when all the monks returned to the monastery, two novices had to do all the cooking and wash the dishes for sometimes well over 100 monks. There was no soap. We had only ashes, rice husks, and coconut husks, and that was all. Cleaning such a high stack of bowls was a chore, especially during the winter when the water was freezing cold. Then you had to heat up a big pot of water before you could do any scrubbing. Nowadays one stands in a kitchen equipped with liquid soap, special scrubpads, and even running hot water which makes it all the more agreeable. It is easier to enjoy washing the dishes now. Anyone can wash them in a hurry, then sit down and enjoy a cup of tea afterwards. I can see a machine for washing clothes, although I wash my own things out by hand, but a dishwashing machine is going just a little too far!

While washing the dishes one should only be washing the dishes, which means that while washing the dishes one should be completely aware of the fact that one is washing the dishes. At first glance, that might seem a little silly: why put so much stress on a simple thing? But that’s precisely the point. The fact that I am standing there and washing these bowls is a wondrous reality. I’m being completely myself, following my breath, conscious of my presence, and conscious of my thoughts and actions. There’s no way I can be tossed around mindlessly like a bottle slapped here and there on the waves.

THE CUP IN YOUR HANDS

In the United States, I have a close friend named Jim Forest. When I first met him eight years ago, he was working with the Catholic Peace Fellowship. Last winter, Jim came to visit. I usually wash the dishes after we’ve finished the evening meal, before sitting down and drinking tea with everyone else. One night, Jim asked if he might do the dishes. I said, “Go ahead, but if you wash the dishes you must know the way to wash them.” Jim replied, “Come on, you think I don’t know how to wash the dishes?” I answered, “There are two ways to wash the dishes. The first is to wash the dishes in order to have clean dishes and the second is to wash the dishes in order to wash the dishes.” Jim was delighted and said, “I choose the second way—to wash the dishes to wash the dishes.” From then on, Jim knew how to wash the dishes. I transferred the “responsibility” to him for an entire week.

If while washing dishes, we think only of the cup of tea that awaits us, thus hurrying to get the dishes out of the way as if they were a nuisance, then we are not “washing the dishes to wash the dishes.” What’s more, we are not alive during the time we are washing the dishes. In fact we are completely incapable of realizing the miracle of life while standing at the sink. If we can’t wash the dishes, the chances are we won’t be able to drink our tea either. While drinking the cup of tea, we will only be thinking of other things, barely aware of the cup in our hands. Thus we are sucked away into the future—and we are incapable of actually living one minute of life.

EATING A TANGERINE

I remember a number of years ago, when Jim and I were first traveling together in the United States, we sat under a tree and shared a tangerine. He began to talk about what we would be doing in the future. Whenever we thought about a project that seemed attractive or inspiring, Jim became so immersed in it that he literally forgot about what he was doing in the present. He popped a section of tangerine in his mouth and, before he had begun chewing it, had another slice ready to pop into his mouth again. He was hardly aware he was eating a tangerine. All I had to say was, “You ought to eat the tangerine section you’ve already taken.” Jim was startled into realizing what he was doing.

It was as if he hadn’t been eating the tangerine at all. If he had been eating anything, he was “eating” his future plans.

A tangerine has sections. If you can eat just one section, you can probably eat the entire tangerine. But if you can’t eat a single section, you cannot eat the tangerine. Jim understood. He slowly put his hand down and focused on the presence of the slice already in his mouth. He chewed it thoughtfully before reaching down and taking another section.

Later, when Jim went to prison for activities against the war, I was worried about whether he could endure the four

walls of prison and sent him a very short letter: “Do you remember the tangerine we shared when we were together? Your being there is like the tangerine. Eat it and be one with it. Tomorrow it will be no more.”

THE ESSENTIAL DISCIPLINE

More than 30 years ago, when I first entered the monastery, the monks gave me a small book called The Essential Discipline for Daily Use, written by the Buddhist monk Doc The from Bao Son pagoda, and they told me to memorize it. It was a thin book. It couldn’t have been more than 40 pages, but it contained all the thoughts Doc The used to awaken his mind while doing any task. When he woke up in the morning, his first thought was, “Just awakened, I hope that every person will attain great awareness and see in complete clarity.” When he washed his hands, he used this thought to place himself in mindfulness: “Washing my hands, I hope that every person will have pure hands to receive reality.” The book is composed entirely of such sentences. Their goal was to help the beginning practitioner take hold of his own consciousness. The Zen Master Doc The helped all of us young novices to practice, in a relatively easy way, those things which are taught in the Sutra of Mindfulness. Each time you put on your robe, washed the dishes, went to the bathroom, folded your mat, carried buckets of water, or brushed your teeth, you could use one of the thoughts from the book in order to take hold of your own consciousness.

The Sutra of Mindfulness1 says, “When walking, the practitioner must be conscious that he is walking. When sitting, the practitioner must be conscious that he is sitting. When lying down, the practitioner must be conscious that he is lying down. . . . No matter what position one’s body is in, the practitioner must be conscious of that position. Practicing thus, the practitioner lives in direct and constant mindfulness of the body . . .” The mindfulness of the positions of one’s body is not enough, however. We must be conscious of each breath, each movement, every thought and feeling, everything which has any relation to ourselves.

How to Love

How to Love The Miracle of Mindfulness

The Miracle of Mindfulness The Miracle of Mindfulness (Gift Edition)

The Miracle of Mindfulness (Gift Edition) The Blooming of a Lotus

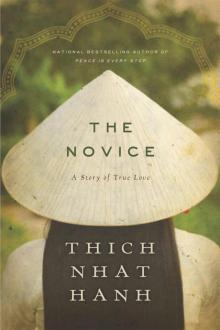

The Blooming of a Lotus The Novice

The Novice