- Home

- Thich Nhat Hanh

The Blooming of a Lotus Page 12

The Blooming of a Lotus Read online

Page 12

7.

Breathing in, there is peace

Peace while

while breathing gently.

breathing

Breathing out, there is

Joy while resting

joy while resting.

8.

Breathing in, peace is

Peace is

the gentle breathing.

gentle breathing

Breathing out, joy is the resting.

Joy is resting

9.

Breathing in, Buddha

Buddha

is breathing gently.

breathing gently

Breathing out,

I enjoy

I enjoy breathing gently.

breathing gently

10.

Breathing in, Buddha is free.

Buddha is free

Breathing out, I enjoy the freedom.

I enjoy the freedom

11.

Breathing in, there is peace

Peace while

while breathing gently.

breathing

Breathing out, there is joy

Joy while free

while feeling free.

12.

Breathing in, breathing gently is peace.

Breathing is peace

Breathing out, freedom is joy.

Freedom is joy

This exercise is to help people relax in either the sitting or the lying position. The one who is guiding the exercise can repeat the phrases as many times as she feels is necessary to induce total relaxation. The important thing is to guide the practitioners in such a way that they do not need to make any mental effort and can relax completely. We can use it for ourselves when we are lying in bed to relax totally as we fall asleep.

Exercise Three

1.

Breathing in, the Buddha

Buddha breathes

is breathing with my lungs.

with my lungs

Breathing out, I enjoy the breathing.

I enjoy

the breathing

2.

Breathing in, the Buddha

Buddha sits

is sitting with my back.

with my back

Breathing out, I enjoy the sitting.

I enjoy the sitting

3.

Breathing in, the Buddha dwells

The Buddha dwells

in the island of self.

in the island of self

Breathing out, I can dwell in

I dwell in the

the island of myself.

island of self

4.

Breathing in, the Buddha has arrived.

The Buddha

has arrived

Breathing out, I enjoy arriving.

I enjoy arriving

This exercise, like the preceding ones in this chapter, is to help us be in touch with the Buddha nature in ourselves directly. It can be used when we are anywhere, even for a very short time, when we need the support of the Buddha.

Exercise Four

1.

Seeing the Buddha before me in

Buddha sitting

the seated meditation position,

I breathe in.

Joining my palms in respect,

Joining palms

I breathe out.

2.

Seeing the Buddha in me,

Buddha in me

I breathe in.

Seeing myself in the Buddha,

Me in Buddha

I breathe out.

3.

Seeing the boundary between

Buddha smiles,

myself and the Buddha disappear as

no boundary

the Buddha smiles, I breathe in.

Seeing the boundary between the one

I smile,

who respects and the one who is

no boundary

respected disappear as I smile,

I breathe out.

4.

Seeing myself bowing deeply to

Bowing deeply

the Buddha, I breathe in.

to Buddha

Seeing the strength of the Buddha

Strength of

enter me, I breathe out.

Buddha in me

This meditation exercise has been applied for more than a thousand years in countries with a Buddhist tradition. In Vietnam, it is used at the beginning of ceremonies before people bow deeply to the Buddha. The traditional wording is: Since the nature of the one who bows and the one who is bowed to is empty, the communication between us is perfect. This meditation is rooted in the teachings of interbeing, emptiness, and nonduality. According to the teachings of interdependent arising, both the Buddha and the person who bows before the Buddha are manifested by cause and condition and cannot exist in separation from the rest of all that is. This is what is meant when we say that both are empty. In this context, emptiness means the lack of an autonomously arising, independent entity. In myself are many elements that are not myself, and one of those elements is the Buddha. In the Buddha are many elements that are not the Buddha, and one of those elements is me. It is this insight that enables me to realize the deep contact between myself and the Buddha, and it is this insight that gives the ceremony of paying homage to the Buddha its deepest meaning. It is rare in religious traditions to find this equality between the one who pays homage and the one who is paid homage stated in such an uncompromising way. When we pay homage like this, we do not feel weak or needy. Instead, we are filled with confidence in our capacity to be awakened in the way that the Buddha was.

This exercise can be practiced in sitting meditation or as we bow deeply before the Buddha, Christ, the bodhisattvas, and so on.

Exercise Five

Mindfulness of the Awakened One

1.

Seeing the Buddha before me,

Buddha before me

I breathe in.

Seeing myself join my palms

Joining palms

in respect, I breathe out.

2.

Seeing the Buddha before me

Buddha before

and behind me, I breathe in.

and behind me

Seeing myself join my palms

Joining palms,

and bow my head in respect to

bowing

the Buddha before and behind me,

I breathe out.

3.

Seeing Buddhas in the ten directions

Innumerable

as numerous as the sands of the

Buddhas

Ganges, I breathe in.

Seeing before each Buddha there

One of me

is an image of myself bowing,

bowing to each

I breathe out.

Buddha

This exercise is a continuation of the preceding one. It has also been practiced for more than a thousand years in the Buddhist tradition. The original wording of the exercise goes something like this: The practice platform that I see before me is the jewelled net of Indra, made of countless precious jewels. All the Buddhas of the ten directions appear reflected in each of the precious jewels, and my own image standing before each of the Buddhas is also reflected in each of the precious jewels. As I bow my head before one Buddha I am paying homage to all the Buddhas in the ten directions at one and the same time. The source of this meditation is the Avatamsaka sutra. It is based on the principle that one is all and all is one. The exercise helps us to see ourselves beyond the scope of the five aggregates, which are always limited by the framework of space and time. It also helps us to see how we interpenetrate every wonder of our universe.

This exercise, like the preceding one, can be practiced in the sitting position or as we bow deeply.

Chapter VII. My Parents, Myself

There are many ways we can usefully apply the teachings of no self in our daily lives. One of the most effec

tive and easiest ways is to see our parents and our ancestors as non-self elements of what we call “myself.” “Myself” is nothing more than an appellation for a whole line of ancestors whom I represent. This truth of no separate self is fully borne out by the findings of science, in particular the science of genetics. In spite of this scientific truth, it is not always easy for people to see that they are their parents. Some people want to have nothing to do with their parents. In fact, if we cannot feel love and compassion for our parents, we cannot love ourselves.

Exercise One

Looking Deeply, Healing

1.

Seeing myself as a five-year-old child,

Myself five

I breathe in.

years old

Smiling to the five-year-old child,

Smiling

I breathe out.

2.

Seeing the five-year-old as fragile

Five-year-old

and vulnerable, I breathe in.

fragile

Smiling with love to the five-year-old

Smiling with love

in me, I breathe out.

3.

Seeing my father as a

Father five

five-year-old boy, I breathe in.

years old

Smiling to my father as a

Smiling

five-year-old boy, I breathe out.

4.

Seeing my five-year-old father

Father fragile

as fragile and vulnerable, I breathe in.

and vulnerable

Smiling with love and understanding

Smiling with love

to my father as a five-year-old boy,

and understanding

I breathe out.

5.

Seeing my mother as a five-year-old

Mother five

girl, I breathe in.

years old

Smiling to my mother as a

Smiling

five-year-old girl, I breathe out.

6.

Seeing my five-year-old mother as

Mother fragile

fragile and vulnerable, I breathe in.

and vulnerable

Smiling with love and understanding

Smiling with love

to my mother as a five-year-old

and understanding

girl, I breathe out.

7.

Seeing my father suffering as a child,

Father suffering

I breathe in.

as a child

Seeing my mother suffering as a child,

Mother suffering

I breathe out.

as a child

8.

Seeing my father in me,

Father in me

I breathe in.

Smiling to my father in me,

Smiling

I breathe out.

9.

Seeing my mother in me,

Mother in me

I breathe in.

Smiling to my mother in me,

Smiling

I breathe out.

10.

Understanding the difficulties

Difficulties of

that my father in me has, I breathe in.

father in me

Determined to practice for the release

Releasing father

of both my father and me,

and me

I breathe out.

11.

Understanding the difficulties that

Difficulties of

my mother in me has, I breathe in.

mother in me

Determined to practice for the release

Releasing mother

of both my mother and me,

and me

I breathe out.

This exercise has helped many young people re-establish happy and stable relations with their parents. At the same time, it has helped them transform accumulated hatred and resentment that began gathering in them at a very young age.

There are people who cannot even think about their mothers and fathers without feelings of hatred and sorrow. There are always seeds of love in the hearts of parents and children, but because we do not know how to water those seeds, and especially because we do not know how to resolve resentments when they are newly sown, both generations often find it extremely difficult to accept each other.

For the first step of the exercise, the practitioner observes herself as a five-year-old child. At that age we are so easily hurt. An overly severe glance or a threatening or reproachful word wounds us deeply and makes us feel very ashamed. When father makes mother suffer or mother makes father suffer, a seed of suffering is also sown and watered in the heart of the child. If this happens repeatedly, the child will grow up with many seeds of suffering in her heart and will blame her father or her mother throughout her life. When we see ourselves as vulnerable children, we learn to feel compassion for ourselves, and that compassion will have a deep impact upon us. We must smile at that child of five years with the smile of compassion.

In the next stage of the meditation, the practitioner visualizes his mother or his father as a five-year-old child. Usually we think of our fathers as strict and severe, hard-to-please adults who only know how to resolve a problem by using their authority. But we also know that before a father was an adult, he was a little boy, just as vulnerable, just as fragile as we ourselves were. We can see that that little boy cringed, fell silent, and did not dare open his mouth to speak whenever his own father fell into a rage. We see that small boy may also have been the victim of the hot temper, scowling, and roughness of a father. It is often helpful to seek out an old family photograph album to find out what our mothers or fathers looked like when they were young children. In our sitting meditation, we can welcome the children who were our mothers and fathers and smile to them as we would smile to dear friends. We see their fragility and their vulnerability and a feeling of pity for them is born in us. When this feeling of pity wells up in our hearts, we know that our meditation is beginning to bear fruit. When we truly see and understand people’s suffering, it is impossible not to accept and love them. The accumulated resentment toward our parents will gradually be transformed as we practice this exercise. As we grow in understanding, so we grow in acceptance. We shall be able to use this understanding and love to go to our parents and to help them transform too. We know that this is possible because our understanding and our feelings of compassion have helped us transform ourselves, and we have already become easier, sweeter, calmer, and more tolerant people. Tolerance and calm are two signs of authentic love.

Exercise Two

1.

Breathing in, my father is breathing

Father breathing

in with me.

in with me

Breathing out, my father is breathing

Father breathing

out with me.

out with me

2.

Breathing in, I am sitting with

My father’s back

my father’s back.

Breathing out, I am breathing with

My father’s lungs

my father’s lungs.

3.

Breathing in, I feel light and at ease.

I feel light

and at ease

Breathing out, Daddy, do you feel

Daddy are you

light and at ease?

light and at ease?

4.

Breathing in, my mother is

Mother breathing

breathing in with me.

in with me

Breathing out, my mother is

Mother breathing

breathing out with me.

out with me

5.

Breathing in, I am sitting

My mother’s back

with my mother’s back.

Breathing out, I am breathing

My mother’s lungs

with my mother’s lungs.

6.

Breathing in I feel light and at ease.

I feel light

and at ease

Breathing out, Mummy, do you

Mummy are you

feel light and at ease?

light and at ease?

There was a day when, in my sitting meditation, I said to my father, who had already passed away many years ago: “Father, we have succeeded.” I meant that we had succeeded in realizing the stopping and peace that is the fruit of meditation. While my father was alive he was a civil servant and hardly ever had the time to practice sitting meditation and feel the joy of stopping. Now as I sat in meditation, I saw that as I meditated, my father was also meditating.

How to Love

How to Love The Miracle of Mindfulness

The Miracle of Mindfulness The Miracle of Mindfulness (Gift Edition)

The Miracle of Mindfulness (Gift Edition) The Blooming of a Lotus

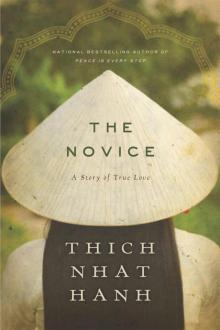

The Blooming of a Lotus The Novice

The Novice